Waking up Partially Dead

part four

The rabbi opened the service with a customary prayer and then began to speak more personally, about what a good citizen I had been, a loving husband and father and devoted grandparent. The regular spiel. Dead people are always praised and made to sound just about perfect. I thought I might like this funeral, although being dead was an adjustment. I loved my life, my family, and my work, and was determined to enjoy my funeral. I leaned against the wall and decided to believe anything flattering I heard about me. I was ready for self-indulgence. How many chances does one have for that luxury?

Although I seldom was satisfied with my accomplishments, I admit I was reasonably successful as a scientist, yet I was always plagued with feeling I hadn’t done enough. But what is enough? Nothing is enough, I guess, if finishing it is required. I was happy when I realized I was truly partially dead, not completely dead yet. I still had a chance to hear myself appreciated.

Rosetta did not want to say anything at my funeral (more than understandable), but my kids spoke, and they moved me. They recalled the many good times we had together and that they loved me. I cried, however since I was dead there were no external tears, just internal ones.

It doesn’t do any good to irrigate driftwood.

The rabbi said a few words about me, adlibbed some mumbo-jumbo, re-anchored his kippah, which kept falling off his head, and turned the service over to the audience. I muttered under my breath, “Uh-oh, we’re in for silence or anarchy.”

I presumed that the service was about to finish and that my contributions as a scientist would remain as buried as I felt them. What can you do? Let the chips fall where they may …life is short, but death is infinite. Maybe another day.

After fifteen to twenty seconds of embarrassing quiet, except for the customary coughing among the mourners, the man next to me raised his hand to speak. I recognized him as a janitor from my graduate school days at the University of Minnesota.

“Please,” acknowledged the rabbi. “My name is Clarence Silvani, and I barely knew the doctor.” So why say anything, I thought.

“He was a graduate student some forty years ago and I was the custodian who cleaned the laboratories early in the morning before anyone came to work. I haven’t seen the doc since then. He wouldn’t have the faintest idea who I am.”

Wrong, Clarence. I recognize you.

“When I read in the newspaper that he passed away, I wanted to come and pay my respects. I don’t have any idea about his work, but it doesn’t matter. Seems that the important thing is that he led a decent life and had faith—you know what I mean. I’ve never been too good with words. When I was cleaning up, I saw students, professors, lots of smart guys. I never did get much of a chance to talk to them. Most I ever got out of anyone was a grunt or an empty,

“How are you this morning?” or “Have a good day.” If I tried to answer their meaningless question of how I was, I’d be speaking to the walls. They never had time to listen to my answer. They didn’t care. I can’t say that I blamed them much. I didn’t care all that much how they were either.

“And then there was the doc, or at least I thought of him as the doc. There were many times that he’d be working at that early hour. He often looked tired. He seemed to care a lot about his experiments. As far as I could tell he was busy as all get-out, and he often seemed sort of worried, but when he asked me, ‘How’re you doing this morning?’ he waited for the answer.

At first, I didn’t say much, but I remember once he said, ‘Tell me, Clarence—is everything okay with you? You look like something is bothering you.’

“The doc knew my name. Can you imagine? It nearly brought tears to my eyes. I didn’t let him know that, of course. It was like I suddenly became more important. “I told him that I was okay, but my wife had this terrible pain in her joints and couldn’t sleep, and that I had a hard time making the mortgage payments. Sometimes we talked about the Vikings, you know—the football team. I loved the Vikings; they made me feel like a winner. The doc knew as much about the players as I did. That’s about it. I never even asked about him. I don’t know, I was just the custodian and all. I never forgot the doc. I just wanted to come here today and give him my respects.”

Clarence stopped speaking and stared straight ahead. I wanted to scream, “Here I am, Clarence, and thanks.” I was standing right next to him, and he didn’t know it. Maybe he did—at least I’d like to think he felt my presence, since he looked directly at me for a moment.

Next, a woman at the other end of the room stood and began to speak. “I was Dr. Reiter’s secretary for ten years. Dr. Reiter worked on the third floor while Dr. Q was on the second floor, so we didn’t have much to do with each other. I saw Dr. Q from time to time when I went down to see his secretary, Patsy. Patsy liked working for him, although she said that he didn’t pay much attention to bureaucratic details, which made her job more difficult.

One day I was walking down the hall and Dr. Q stopped me and said, ‘Emma, everything all right?’ That’s all. It was like he sensed something, like he did for Clarence. I did have a problem. Since my defenses were down, I started telling him about my difficulties, and he listened. He asked if I wanted to go to his office where it would be more private. I was embarrassed, but agreed, and we talked for about ten minutes. I told him that my six-year-old son was not getting along at school and was depressed and anxious. My friends always gave me a pep talk and said that my son would outgrow his depression, although I had no idea how they would know this, and they told me about their kids, and that I was a great mom, that kind of thing. But Dr. Q understood how difficult this was for me and instead of a pep talk he gave me the name of a psychologist, a friend of his. I know it doesn’t sound so fantastic, but believe me, if it wasn’t for him and that psychologist, my son may not have become the successful banker and family man he is today. Thank you, Dr Q. I hope that you can hear me.” And she sat down.

Yes, you’re right, it’s not so fantastic, but you’re welcome. I remember the episode. I hardly gave it a second thought. It wasn’t such a big deal to recommend a friend to someone in need. It’s all in a day’s work, as I see it.

Another person rose. “I … I … I just wanted to say something, but it’s kind of silly. My name is Dr. Robert Hall and I’m the pharmacist where Dr. Q got his prescriptions filled. He was always in a rush, always said that I had to fill it quickly because he had a lot to do. Seems he even rushed to die. But there’s one thing about him that was special. Lots of doctors snub us pharmacists like we’re just some kind of commercial tool or messenger delivering the doctor’s orders. But after I talked for a few minutes to him, when he had time that is, I always felt good about myself. It didn’t really matter what we talked about—sports, cars, work, the weather, just about anything. I don’t have any idea why it was, but afterwards, I felt a little bit more significant. That’s it. He made me feel significant. I tried to get his prescriptions as quickly as I could, so he didn’t have to wait too long.”

Bob Hall is right about that, I was always in a hurry, and that’s because the guy was slow as molasses. I’m happy that he felt significant after talking to me, but don’t ask me why.

When Professor Martin Hildebrand, a long-term colleague from Yale, stood up I thought I would finally hear something substantive about myself. He’s one of the most respected scientists in the country with all sorts of honors—a superstar. I remember leaning forward to make sure I heard every word that Martin said.

“I’ve known Dr. Q for over thirty years,” he said. “We met first at a scientific meeting in Italy and our wives became friends as well. We saw each other socially as well as professionally. He had an easy-going personality, rather laid back, as if he didn’t care that much about his work, but I do think he cared. He always made things easy for me. When I called, he called back immediately if I left a message. If I needed for him to do something for me, such as write a letter for something, he would do it without delay. He was a steady guy. I never mistook his willingness to help for subservience. He’ll be missed.”

Professor Hildebrand sat down looking like he’d fulfilled his obligation. Subservience! Who does Martin think he is? Laid back? Don’t care about my work? A steady guy? What does that mean, that I have good balance? What about the time he didn’t know how to interpret his data until I figured it out, and then he published it without acknowledging me? I’ve had it! Martin seems to have cared for me to some extent, when he wasn’t caring for himself that is, and he did come to my funeral. But … what he didn’t say screamed in my ears, loud and clear and frankly, I’m pissed! Suddenly I feel alive again, and it’s exhausting. Maybe it’s better to be dead.

Finally, after a short pause, a tentative voice came from along the wall. I didn’t recognize the voice. Who was this guy? “I never met Dr. Q,” started the stranger.What the heck does he want to say? “But I am here today because of him.”

Of course. Everyone goes to a funeral because of the dead guy; thank you very much. “I came from Russia, and the immigration department was about to deport me due to an expired visa. I needed a green card to stay in this country. I came with my family, and it was very scary, very difficult for us. Since I study eyes, like Dr. Q, and he was well known, I sent him an email and asked him if he would write a letter of recommendation and help me stay in this country. I couldn’t believe it when he responded within a day, a busy man like that. He asked me to send him any information that would help him know what he could say about me. A few days later he emailed me and said he had written a strong letter on my behalf and wished me luck.

Soon after I was accepted for a green card. I’m sure that was because of him. “Today I am an associate professor at Boston University and a U.S. citizen with an American family. I wrote to Dr. Q to thank him, but I still never met him. I did meet a guy from the immigration department by chance who said he remembered that letter, that unpublished document, those life-saving words that were written for bureaucrats and never seen by anyone else, his letter to help a desperate immigrant from Russia. He said that the letter summarized my work, which Dr. Q obviously took the time to read about, and stressed the promise my research held for advancing treatments for eye disorders. The letter also said, and I quote by memory because it impressed me enough to remember the exact words, ‘… that the U.S. Immigration Department has a simple choice, to enrich this country with a devoted scientist, an honest man who wishes to maximize his potential, or to miss this opportunity and send him back to Russia.’ I never had such a friend. I am so sorry that I never met him.”

For whatever reason, this eulogy got to me. My sarcastic streak was left floating in the breeze. I was filled with genuine pride that I had helped this man. I wanted to hug my Russian—now American—“friend.”

Without warning, Martin Hildebrand, and science, and ambition all flashed through my mind, all mixed in no specific order, and left me disoriented for a moment. How surprising to discover by the offhand comments of a stranger I never met, that I truly helped someone, him.

Martin’s image faded and was replaced by that of Clarence, and Patsy, Dr. Reiter’s secretary, and the Russian immigrant, and even the pharmacist Robert Hall. I felt at peace and satisfied, not because I was dead, but because I had lived.

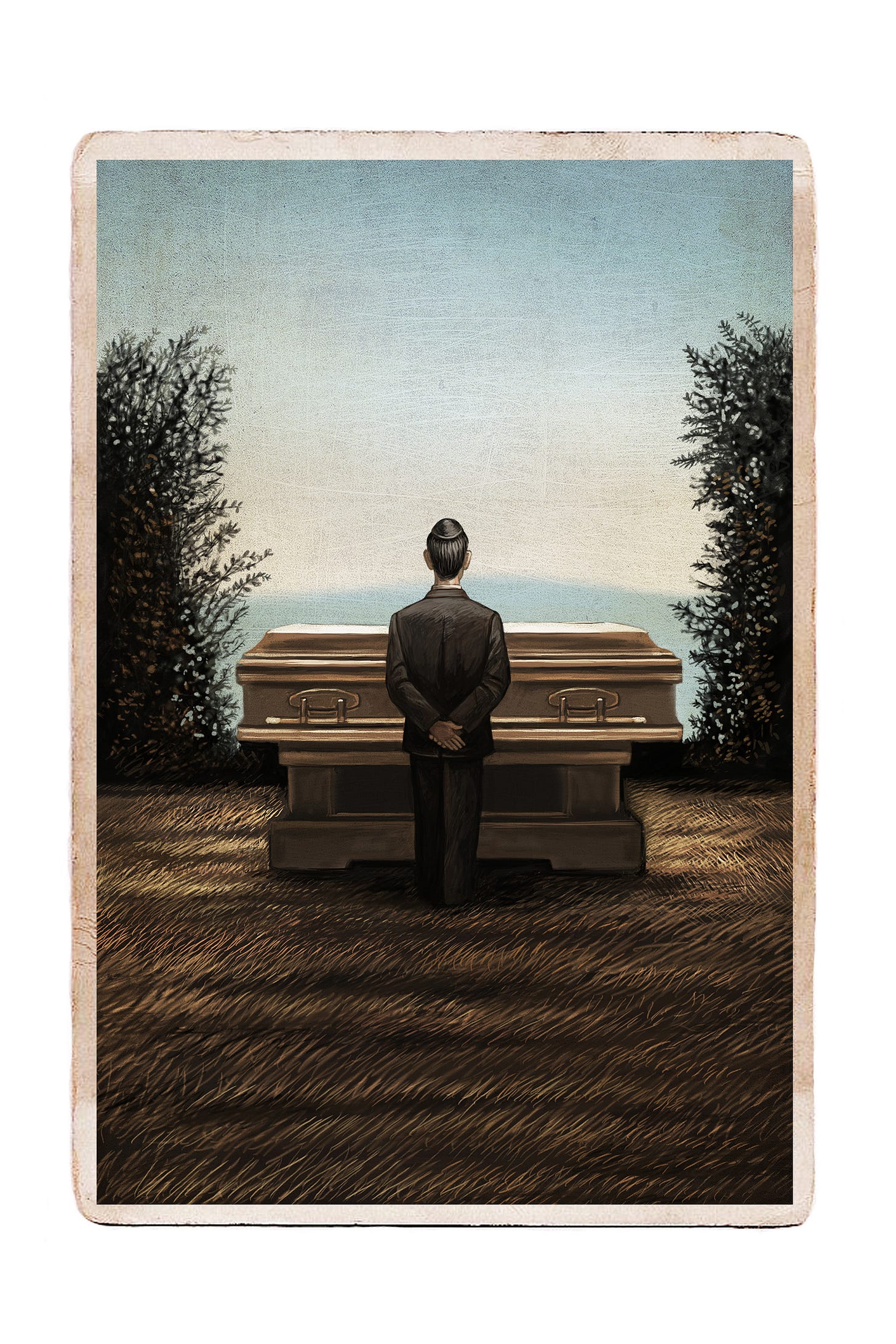

The rabbi returned to the bimah and gave a short prayer. He invited everyone to the burial in the cemetery outside of the temple. Suddenly I wasn’t standing against the wall anymore. Rather, I was lying in my coffin, which was more comfortable, and a group of fully alive men carried me out. A small group came with me.

I knew most of the people at the cemetery but there were also some that I had never ever laid eyes on. I didn’t know whether being fully dead now erased my memories of them, or whether there was another explanation. I always had trouble recognizing faces. Or perhaps they were strangers I had helped as I did the grateful Russian. Few fellow scientists who took the trouble to go outside in the cold for the burial, except for a couple of my students, who looked genuinely sad. Martin was not there; neither was Sam.

I was lowered into the ground by a small crane. My world was black now, and very quiet. I worried that such cramped conditions would be claustrophobic, but surprisingly it didn’t bother me. Dying was an adventure, a new experience, a different environment and set of emotions.

I wondered how I would know for certain when my death was final, since I find myself at peace but still thinking. Will I come back to life in some fashion as a different person or stop thinking altogether, or return as some kind of animal or as another partially alive tourist here for a visit? I never believed in reincarnation, but who knows? I’m no longer sure about anything. If I can be partially dead and still function, I guess anything could happen when one steps into the unknown. What form would I be if I returned: a bacterium? a giraffe? a person? A man or a woman? A woman would be interesting for a change.

I’m an atheist and don’t believe in heaven or hell, but if I’m wrong, I hope it’s heaven. Dying is impressive and ordinary at the same time. Life and death. Maybe they’re both the same thing and special in the same way that everyone is special: elite by commonality. Ironic. A paradox, as is our short time on this planet. Let the chips fall where they may. One never knows, does one?

Goodbye. Unfortunately, I won’t see you later—or will I?

The end